A 2mm YouTube Project (I)

Here’s my outline for a new video wargame project: a 2mm replay of the 14 January 1797 Rivoli battle: a relatively small but decisive encounter between French troops under Napoleon, and Austrians commanded by Alvintzi. Italian campaign, Napoleon succesfully fends off Austrian armies who are trying to relieve their garrison trapped in Mantua. Outcome: battle lost, Mantua lost, Austrian backyard wide open, war lost for the Austrians, Napoleon is the hero.

Prelude: 1796

In Spring 1796, Napoleon first defeated the Piedmontese army and drove Austrians back. Napoleon addressed his men on April 26, 1796: “Soldiers! In 15 days you have gained six victories, taken 21 standards and 55 guns, seized several fortresses, and conquered the richest parts of Piedmont. You have captured 15,000 prisoners and killed and wounded more than 10,000! … Thanks be to you, soldiers! … You all in returning to your villages will be able to say with pride: ‘I was of the conquering Army of Italy.’”

The campaign was not over, though. The Holy Roman Empire, later the Austro-Hungarian Empire, reorganized and was determined to teach the “weak” French and their young general a lesson. In September, an Austrian army under Würmser retreats to Mantua and the French decide to besiege the city. The Austrians launch several rescue operations and try to get support from the Papal forces.

Don’t shoot the messenger… but Napoleon does

In early January 1797, Lieutenant Celso Gallenga of the French 7th Hussars led a half-troop of cavalry on a reconnaissance mission that would have a profound effect on the war between Austria and France. ‘My advance party took a prisoner,’ he recounted, ‘…a young gentleman, who was a cadet in Strasoldo’s Regiment. The sergeant reported to me that as they surrounded him they saw him swallow something, from which I naturally concluded that he was a bearer of dispatches and could give important information. I therefore hastened back with him to headquarters.’

The prisoner, however, maintained that he knew nothing when interrogated by Gallenga’s commander, General Napoleon Bonaparte.

‘I must have the dispatch,’ said General Bonaparte. ‘Shoot him!’

‘But sir,’ protested Gallenga, ‘he surrendered to me as a prisoner of war, and in uniform.’

‘Lieutenant,’ said the general, ‘there is room for two men in front of a firing squad.’

Wrote Gallenga, ‘It was less the threat than the look that accompanied it, which awed me to silence.’

While Gallenga correctly took the measure of Bonaparte’s determination, the young cadet did not. He continued to deny any knowledge of the dispatch. Immediately after the prisoner was shot, recounted Gallenga, ‘a surgeon opened the corpse, and found the dispatch wrapped in a ball of wax.’

Gallenga’s account says much about the character of Napoleon Bonaparte — and his urgent need for information. In January 1797, the 28-year-old general and his Army of Italy faced two serious problems. First, an indefatigable Austria, recovering from its defeat at the hands of Bonaparte at Arcola in November 1796, was raising yet another army to drive the French from Italy. Second, Pope Pius VI had broken his armistice with Revolutionary France and was re-mustering his Papal army against it.

Against that backdrop, the contents of Gallenga’s captured dispatch were of great importance. It held an order to Würmser to break out southward from Mantua if he could not hold the town any longer, then cross the Po River and take command of the combined Austro-Papal forces. Bonaparte now knew that he faced not only an Austrian offensive from the north and east but also the real possibility of a Papal attack from the south. The information came just in time. The next day, January 8, 1797, Austria opened its offensive by attacking French outposts on the lower Adige River.

But Napoleon was ready.

Setup

Short summary:

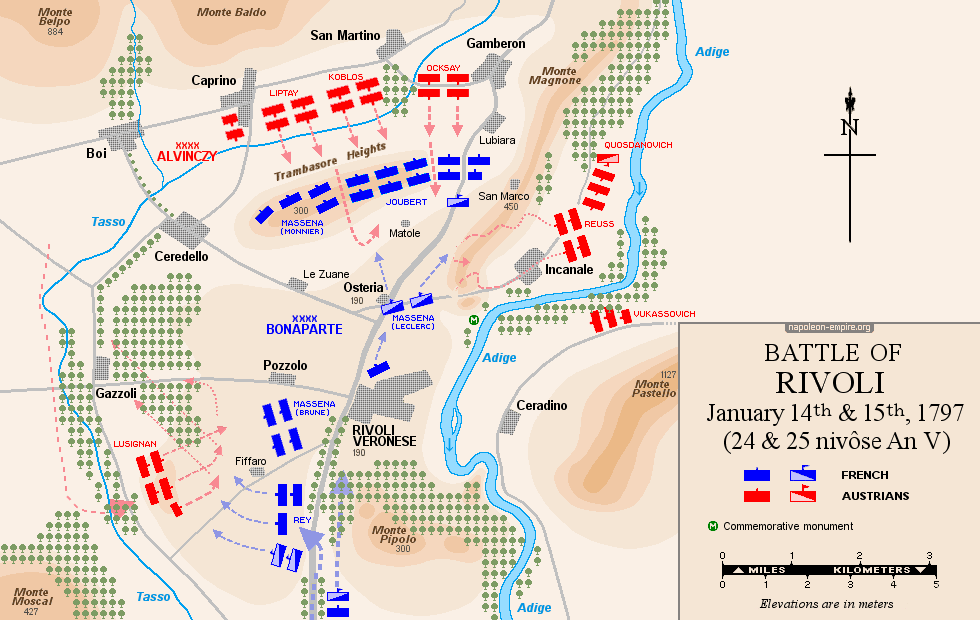

The Rivoli site forms a semi-circular plateau surrounded by low heights but with rather steep slopes. It’s a good defensive position and hard to enter with artillery and cavalry from the north and northwestern side. The Austrian commander Alvinczy divides his troops in six columns.

- Lusignan’s column below Gazzoli, right flanking maneuver

- Liptay in the center

- Köblös in the center

- Ocskay’s column supporting Liptay and Köblös

- Cavalry and artillery in Quasdanovich’ fifth column near Canale, flanking maneuver

- The 6th (Vukassovich) column was in charge of seizing the fort of La Chiusa, of throwing a bridge over the river and of startling, just as Lusignan but by the other wing, on the rear of the enemy.

The synchronization of all these Austrian maneuvers, in the middle of winter and in a mountain region, is a challenge that would not be kept.

Napoleon knew that reinforcements were coming so he had to hold out as long as he could. [Waterloo had a similar tactical disposition, but for the Anglo-Allied troops].

Course of the battle

At 4:00 a.m. on January 14, without waiting for Massena’s division, Bonaparte ordered Joubert to retake any ground that had been lost the previous day. This caught Alvinczy completely by surprise, for he had expected the French to remain on the defensive. Bonaparte decided to immediately seize the heights of San Marco because it was the key to the plateau. Alvinczy struck back.

The strong Austrian center threatened the weaker troops commanded by Joubert in the French center, so Joubert tried to drive Liptay, Köblös and Ocskay back, early in the morning. They failed. After several hours of fighting the French had to retreat. The Austrians under Quasdanovich slowly entered the plateau via a steep slope. On the surface, the situation looked bad for the French.

However: the Austrian center columns were exhausted by the battles fought since dawn; Quasdanovich only had a very small amount of troop on the plateau while the rest of his men were engaged in the difficult climb of the slope; while Lusignan was still very far from being able to intervene.

What did Napoleon do? He sent a demi-brigade forward to slow down Lusignan. He focused his attention on Quasdanovich, and sent reserve cavalry commanded by Lasalle and a demi-brigade, in close formation, on Quasdanovich’s head of the column. Zapp! Kaboom! Austrian column on a slope in disarray. Intense cannonade by French 15-piece battery. Unexpected explosion of two caissons of Austrian artillery, in the midst of the crowd of fugitives. Total carnage. The 6th column under Vukassovich, fled, too.

The battle is a typical display of Napoleon’s ‘punch them one by one’ tactics. The Austrian center was already under pressure, and exhausted, and now suddenly reinforcements who had crushed Quasdanovich showed up in their flank. They panicked and ran away. Liptay understood that the center position was lost and retreated.

Then Lusignan. This Austrian commander ignored the bad signs from the rest of the battlefield and entered the arena, too late. His column got attacked and encircled by the French. Lusignan himself managed to escape by Lake Garda with some companions. That’s all that remained of the 5,000 men entrusted to his command by Alvinczy.

Aftermath

Bonaparte did not sleep on the battlefield. Being informed that another army under the command of Provera was now in sight of Mantua, he entrusted Joubert with the pursuit of the Alvinczy(which Bonaparte’s subordinate duly embarked on, clashing again with Alvinczy on the fifteenth) and then himself rushed with Masséna’s and Victor’s divisions to face the new threat. They marched all night to prevent Provera to relieve Mantua. That other Austrian rescueing force, attacked on two sides, was smashed as well near La Favorita (16 January). Meanwhile, the French near Rivoli routed the retreating Austrians under Alvinczy.

This last episode represented the outcome of a battle in which the Austrian losses amounted to 14,000 soldiers out of the 28,000 engaged, of whom nearly 10,000 laid down their weapons. The French, 20.000 strong, for their part, had in all just over 3,000 killed, wounded and prisoners.

The Rue de Rivoli, a street in central Paris, is named after the battle.

(A more detailed background and summary of the battle can be found here online).

Oldmeldrum Wargame Scenario’s

I like Blücher and I normally play it with my 6mm miniatures. The volunteer Oldmeldrum Wargames Group publishes cheap, really professional Blücher scenario’s online, Rivoli was just 2 dollar, that will be donated to a Veterans Trust. I recommend their work.

Rivoli in 2mm

My 6mm armies are late war shako armies. Every grognard would detest me if I would use these miniatures :-). Since COVID I have a nice portable Blücher army in 2mm. Suitable for every bicorne and shako army between 1792 and 1815. I played a Rivoli wargame earlier, with those figures, and it was just as simple as a 6mm or 20mm game. The scale allows you to recreate the battlefield and the grand scale movements in a convincing way.

Video clip

To promote our club, Napoleonics, Blücher and the improbable 2mm scale I plan to shoot a film and vlog it.

Painting armies is fun, but making small military history / wargame vlogs is just as creative. New aspect of my wargaming hobby.

Masséna

Napoleon was in command, but Masséna contributed a lot to this victory and the subsequent victory at La Favorita. During the two years in campaigns against the Austrians in Italy, Masséna was a genius in maneuvering his forces over difficult terrain. In this Rivoli battle, his troops were a wedge between the Austrian center and Lusignan, important in rolling up the center columns and the column of Lusignan.

He was valiant. At Rivoli, he personally tried to rally the French troops, even striking some of them with the flat of his sword. He could not stop the retreat and soon found himself alone with adjutant Paul Thiebault and an aide-de-camp. Thiebault said it was time to be going, but Massena stayed there, whistling while he watched the Austrian skirmishers. [COOL].

Finally, he took off at a gallop and placed himself at the head of the 32nd, which was marching forward with a forbidding resolve.

In the aftermath of the battle, he manoeuvered with Napoleon in a forced night march to La Favorita where they crushed a second Austrian army the 16th of January.

Lasalle

Italy and the battle of Rivoli was the flying start of the career of Antoine Charles Louis de Lasalle, the famous cavalry general, a legendary hussar, hero and womanizer, a 1797 James Bond. He was captured by the Austrians early in the campaign, who interrogated him about Bonaparte, the new general-in-chief. How old is Bonaparte?, the Austrians asked, in disbelief “Older than Scipio when he besieged Hannibal”, Lasalle snapped. In January 1797 he had an affair with an Italian princess behind enemy lines. He sneaked through the lines, kissed his lover, got all-important information from her about the strength of the Austrian army, and galloped back chased by a full squadron of Austrian hussars. He escaped them all. At Rivoli he frontally assaulted Quasdanovich’ column with just 26 French hussars – and forced the panicked Austrian column to capitulate. Suicidal, but he survived, just like 007. According to the legend, Napoleon said, when Lasalle returned to him with all the captured flags: “Lay down and sleep under them – you earned it.”

Lasalle died during the Wagram battle, 1809, a shining star among Napoleon’s cavalry generals.

Love this! Lasalle; what a guy!!!

LikeLike